Audio

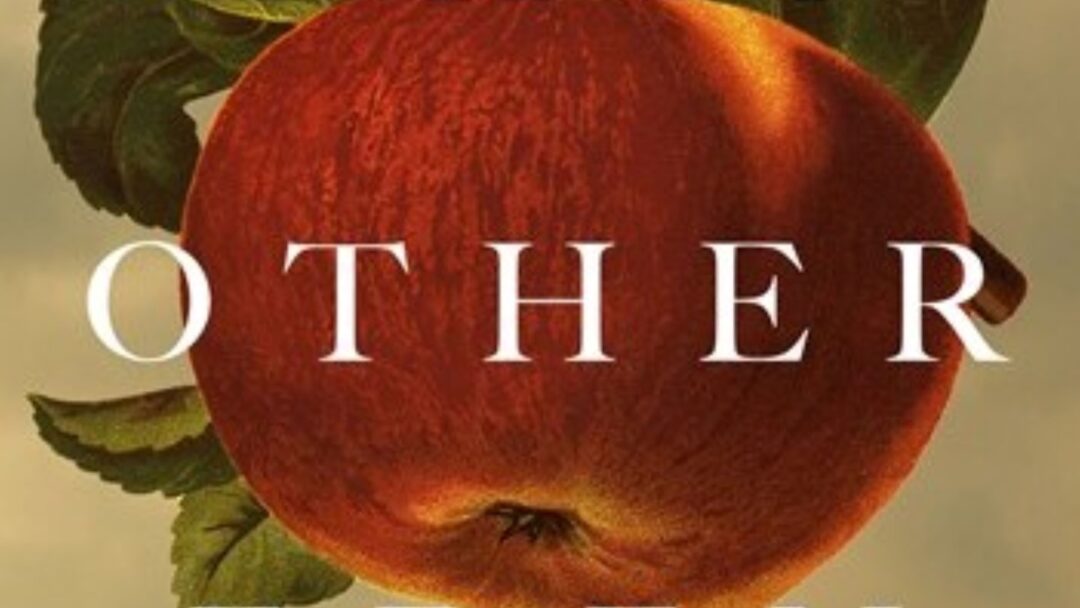

Girl with a Pearl Earring

Hear This by

Vision Australia3 seasons

8/9/2023

28 mins

Hear This interviews Tracey Chevalier, author of Girl with a Pearl Earring.

Hear This reviews latest books from the Vision Australia library for people who are blind or have low vision. Presented by Frances Keyland.

This episode Frances interviews Tracey Chevalier, author of Girl with a Pearl Earring.

00:11UU

You. Inside the book.

00:24S1

Hello and welcome to hear this. I'm Francis Kelland and you're listening to the Vision Australia Library Radio show on Vision Australia Radio. It gives me great pleasure this week to present an interview with Tracey Chevalier. Tracey burst onto the literary scene in 1999 with her historical novel Girl with a Pearl Earring, based on the famous portrait by the artist Johannes Vermeer, who lived and worked in Delft, Holland, during the 1600s. No one knows who the subject of the painting was, but her direct gaze at us over her shoulder with the light softly touching the drop Pearl Earring adorning her left ear, has begged speculation for centuries. Who was she? Chevalier has created Grete, a servant girl with artistic talents of her own, and planted her in the artist's household, where she becomes a helper in Vermeer's studio, as well as juggling the usual duties of helping to run a household as a lowly servant. In this novel, she is the subject of the painting since then, Chevalier has continued to write rich and observant historical novels with characters that draw us into their worlds. For her latest book, New Boy, published this year, she's gone into more modern times. This book is set in the 1970s and uses Shakespeare's Othello as a template. Tracy is in town for the Melbourne Writers Festival. But before she left London she was able to talk on the phone with me and I hope you enjoy our chat. A big welcome to you. Tracy Chevalier Thank you for coming on to the radio with us.

01:56S2

It's a pleasure. Thank you.

01:58S1

Now, I will start off by asking you about your second novel that followed The Virgin Blue. It's The Girl with a Pearl Earring. And in this, through writing this book, you created a new fan base for Vermeer, and the novel then became a movie and a play. Was this a hard act for you to follow as a writer?

02:17S2

Yes. I mean, I think what was hard for me was that suddenly there was an expectation outside of just myself. So when I wrote Girl with a Pearl Earring, I wrote it in a bubble. Nobody knew who I was. Nobody knew that this book was was going to be happening. And and after that, suddenly everybody did know and readers and publishers alike were saying, Right, what's in it? What's the next one going to be? And, you know, you can go down two routes, you can repeat yourself. So maybe I could have done a different painting or stayed in 17th century Holland or written another a sequel. But or the other route to go is to do something completely different. And that's what I did and that's what I've done ever since because I don't want to repeat myself. I always want to learn. I want to find out about other subjects and write about different topics. So I. I followed it up by writing something, a novel called Falling Angel, set in early 20th century London in a in a cemetery, so it couldn't be more different.

03:23S1

And what draws you to history?

03:25S2

I think the first thing about it is, is oddly enough, that it takes me away from myself. So I'm not writing about my life, about my concerns. I'm throwing myself out into the world. And as I get older, I start to understand that I'm living in a continuum. So I'm not living in just the present. There's there's the future, of course, but there's also the past that extends, you know, thousands of years behind us as human history. And and I feel like I've become a bigger person when I know more about the past and and understand how insignificant I am. It actually maybe paradoxically makes me feel better, makes me feel like more I'm part of a a bigger picture. And so I've been turning backwards back ever since. My first novel, The Virgin Blue, was partly contemporary, but partly historical, and I discovered then that I really loved writing the historical sections because I could leave myself behind and immerse myself in a different world. And I've been doing that ever since.

04:31S1

Because in your books, the only really the things that are immortal are the objects, whether it's a work of art or a fossil, a gravestone. These objects in your books have a potency where the characters revolve around them. Is this a personal experience you have with objects or artwork?

04:50S2

Yeah, I think so. I'm always very aware that we are so transient as humans, but we leave behind an awful lot of things. So yes, art and fossils or whatever, medieval tapestries, the cemetery, all of these things way outlive humans. And I find that objects have a kind of talismanic quality to them and that makes them really important to me, especially in this day and age. You know, we look at things so much on the computer, but. You can look at a copy of Girl With a Pearl Earring on a computer. And but it's nothing like actually being in the room with that painting. It's just so powerful. So I always try, if I can, when I'm writing to see the the objects and the places that I'm writing about. I know some writers managed to do it without it. You know, they use Google Earth or whatever, but but not me. I have to be there now.

05:50S1

Your characters are written in the first person narrative and they're all entangled in subtle and not so subtle interactions based on class society, how self-aware they are. And you often swap characters voices over the books, the book chapters. Is this a fun part of the writing process?

06:07S2

It depends. I usually find some characters easier to write than others. I usually the characters in a way who are very, very definite and and their voices are definite and I can hear them even before I write those days when I'm writing them, I think, Oh yeah, this is going to be an easy day and other days are harder. It just depends upon where where I am in the book. And sometimes a character might be a little more subtle or might be changing in a way that I find hard to capture. I mean, I, I love writing, but it's a hard process. I feel every day that when I write, I've got the platonic ideal in my head and then what comes out on the page is always a bit of a compromise. And maybe all people who create things feel that way. You might be knitting a sweater or painting a painting or or carving something and you know, sort of what it is you're trying to achieve. But what you actually end up with is, is always a little bit different. And and that can be quite hard.

07:11S1

So that's living with a feeling that what you've done isn't perfect, is.

07:17S2

That, Oh gosh, yes. I feel like I fail all the time. I probably I'm on my own worst critic, but I failed. It didn't stick and say failed and fail better. And so I'm trying to fail better as every book.

07:31S1

The psychology of your characters is so real and it's a real point where we can enter into the history because we become, through their eyes, experiencing all of those social mores of the time and the restrictions of the freedoms. Where did this interest in psychology come from, or do you have an interest in psychology?

07:50S2

I, you know, not specifically, but I think as a human being, I think we all do. I hope we all do. I would find it a very boring life if I wasn't interested in other people and how they tick. And and I guess I just assume that everyone else is like that, too. At least my readers, I hope, are like that. That's why they read. That's why you turn a page. Turn pages. To finish a book is you want to find out not just what's going to happen, but what's going to happen to the characters, because they've become real people to most readers. And and I think it's human. It should be in human nature to care about what happens to other people, to be curious about what what's going on in someone's head.

08:33S1

Do you have a favorite historical period or if you had an opportunity to time travel once, what era or country, what era do you choose as your destination?

08:44S2

Oh, that's a good question. I think I would I would love to go and and be a silent witness in Vermeer's painting studio. So 17th century Holland. I feel like I know the period very well. It's been well documented by paintings, but I'd still like to, to watch him at work and see what the city is like that Delft that he lived in. So that's where I go.

09:13S1

And your latest book, which is based on Othello, is set in 1970s America. Did the idea of setting a book in the 1970s, was this exciting or daunting?

09:23S2

It was exciting. You know, I was ready for a change. I was asked by a publisher to take part in this thing called the Shakespeare Project, where authors choose a novel, a Shakespeare play, and turn it into a novel. And I could set it whenever, wherever I wanted and and whenever. For once, I decided to write, to set it in a period when I was alive. So the book is is set on a school playground and all the characters are 11 years old and it's set in 1974 in Washington, D.C. And that's where I grew up and when I was 11 was in 1974. So it's not autobiographical. Obviously. It takes place during a period that I remember well from from my childhood, and I was laughing afterwards or during it at how easy it was. Instead of having to do all the historical research, which is a big part of my of my job as writing historical novels, you know, I just had to remember I just didn't remember what I wore and what I ate and what. We chanted when we jumped double Dutch and what kind of lunchbox we had. And all of those little details just floated into my mind. I didn't have to go to the library and read a book to figure it out, and that was kind of wonderful. It was also an interesting what I would say is the first draft was an interesting intellectual exercise turning having been given basically given the characters in the story and then told to, you know, I had to reset it somewhere that was like an exercise. And then the second draft I had to make it into a Tracey novel and have it come more for the from the gut. And I think that's where the setting really kicked in because I just had such memories of my time as a kid and what it's like. The book is about a boy, a black boy walks onto, he's a new boy and he walks out onto an all white school playground. And it just brought back memories of what it's like to be a new kid and what how we felt about race at the time. And I think it was it was it was a lot of fun to do. I wouldn't say it was daunting. Exactly. What was more daunting was not the setting, but I think addressing Shakespeare at all. You know, I felt I wanted to respect what he did and but also make it my own. And that was quite daunting.

11:43S1

Have you ever thought of taking on something else like the Mona Lisa or anything or any other, like, really famous work of art?

11:52S2

Okay, so you're not the first person, I'm sorry to say, who has suggested we take on the role of the. Lisa. You know, that's just not the way I normally come up with ideas. I don't normally sort of think, okay, what shall I do an artwork now and what shall I do? Or so that's why the Shakespeare Project was so unusual for me. And I think that it was fun to do. But I'm I prefer to let the ideas come to me and sort of jump on me unawares. I don't plan them out. So I have ideas by I'll be going around a cemetery with a friend on a on a tour and think, Oh, I've got to set a novel here. I went into a dinosaur museum and I found out about a woman who wrote who collected fossils, and I thought, I must write about her. And so I never really know where my ideas are coming from, but. And who knows, I might write about another painting someday, but I might not. I just have to see what happens.

12:50S1

And what are you looking forward to in your trip to Australia?

12:53S2

Oh, well, I've only been to Australia once before on a book tour and I'm. I'm looking forward to seeing some friends again. I have friends in all the cities I'm going to, which is great because I haven't seen them because they're all so far away and it's just getting to meet my Australian readers and I have some free time in each of the cities I'm in, which which is also great. It means I can hang out and wander the streets and have a coffee and just just enjoy the sunshine and the and the being very, very far away from my life.

13:28S1

I hope the sunshine is out for you. We're freezing here at the moment. We've had a very cold winter, so. Oh, no. Yeah. So I hope we don't disappoint you there.

13:38S2

Where. Where are you. Where are you phoning from? Which city?

13:41S1

I'm in Melbourne at.

13:43S2

Auburn and it's cold.

13:45S1

Very cold. Well for for us it is. It's just very cold. You couldn't sit comfortably outside at a cafe. Probably. What?

13:53S2

What temperature is it.

13:54S1

Oh, for us cold. It's about, oh. 12°C. Right. Okay. Yeah. Okay.

14:00S2

Yeah, that's that's that's normal here. So. Okay. I just have to pack accordingly. Yes.

14:06S1

Yes. And you know, you might. You might be tougher than we are. Oh, it's been lovely talking to you. Tracy Chevalier, thank you so much once again for taking your opportunity. I think a few of us here from the library are going to go and see one of your sessions at the Melbourne Writers Festival this year. But I just wanted to ask you, because our readers, as I've mentioned earlier, are blind or vision impaired. Have you got any blind characters in your novels?

14:32S2

I do. I have two. One is in The Girl With a Pearl Earring, The main character, the girl in the painting. Her name is Grete, and her father has been blinded in an explosion. And I actually made him blind for a particular reason because I wanted. I wanted Grete to have a reason to describe the paintings she's seeing. She works as a servant for the painter of Vermeer, and I wanted her to have to describe the paintings to somebody. And it made perfect sense that her father would be blind and that's why she would describe him. And rather than say, draw them out or something. And so that that was that reason. And then I wrote a novel called The Lady and the Unicorn, which is about a set of medieval tapestries and in the Weaving family. We were making the tapestries. The daughter Eleanor, is blind and she can tell apart. She helps out by telling. She could tell apart the different colors of the wool, by feel and by touch and touching them because the the dyes have it slightly different. Give each bit of wool, a slightly different feel. And I actually sort of made that up. And then afterwards a blind reader wrote to me and said, How did you know I do that all the time when I'm shopping for clothes? And I was I was amazed. And I thought, that's that's when, you know, you're on the right track, when when you make something up. But you feel like you're so immersed in in, in faction things that you get it right. You guess it right. So I was I was really pleased about that.

16:12S1

It's also, again, going back to the psychology question, I guess that was what I meant more that you have an insight that seems to come into the books with your characters that rings so true. And that's just a perfect example of what you call a guess or to me, probably being humble. It's probably more an intuitive feeling.

16:34S2

Maybe. Yeah. I mean, I spend a lot of time with my characters either in my head or actually writing them, and and that makes me get to know them both physically and psychologically pretty well. And and I think when I don't know characters, well, you can tell. And so that's part of the reason it takes me 2 or 3 years to write a book. I can't just rush it without knowing the characters. I have to I have to get to know them very well. And and then I suppose the intuition just kicks in quite naturally.

17:07S1

Once again, I'm saying goodbye for the second time. But thank you so much for taking the time and, and let's pray for warmer weather in Melbourne. And thank you very much, Tracy Chevalier, for joining us.

17:19S2

Thank you.

17:21S1

Historical fiction is one of the most popular of our genres in the library. And we have four of Tracy Chevaliers books in the collection. The first one, Girl With a Pearl Earring, of course, we talked about in the introduction when an accident at work destroys her father's livelihood, 16 year old Grete is forced to become a maid to a rich family. Her master is the famous painter Vermeer. One of her duties is to clean his studio, during which she realizes that she also has an eye for the color and light needed to create Vermeer's masterpieces when he himself discovers her talent, greets precarious status within the household, comes under stress. And as his fascination grows, so do Greeks problems. Let's hear a sample now of this wonderful novel narrated by Patricia Jones.

18:07S3

My father wanted me to describe the painting once more. But nothing has changed since the last time I said. I want to hear it again, he insisted, hunching over in his chair to get nearer to the fire. He sounded like Franz when he was a little boy and had been told there was nothing left to eat in the hot pot. My father was often impatient during March, waiting for winter to end the cold, to ease the sun to reappear. March was an unpredictable month when it was never clear what might happen. Warm days raised hopes until ice and grey skies shut over the town again. March was the month I was born. Being blind seemed to make my father hate winter even more. His other senses strengthened. He felt the cold acutely smelled the stale air in the house, tasted the blandness of the vegetable stew more than my mother. He suffered when the winter was long. I felt sorry for him. When I could, I smuggled to him. Treats from Tanaka's kitchen. Stewed cherries, dried apricots, a cold sausage once a handful of dried rose petals I had found in Katrina's cupboard. The baker's daughter stands in a bright corner by a window. I began patiently. She is facing us, but is looking out of the window down to her. Right. She's wearing a yellow and black fitted bodice of silk and velvet, a dark blue skirt and a white cap that hangs down and two points below her chin. As you wear yours? My father asked. He had never asked this before, though I had described the cap the same way each time. Yes, like mine. When you look at the cap long enough. I added hurriedly, you see that he's not really painted it white, but blue and violet and yellow. But it's a white cap, you said. Yes. That's what is so strange. It's painted many colors. But when you look at it, you think it's white.

20:24S1

So that was Girl with a Pearl Earring by Tracy Chevalier. We also have this book in Braille. The first book that Tracy ever had published was called The Virgin Blue. Meet Ella Turner and Isabelle de Moulin. Two women both born centuries apart, yet tied together by a haunting family legacy. When Ella and her husband moved to a small town in France, Ella hopes to brush up on her French qualify to practice as a midwife and start working on a family of her own. Village life turns out to be less idyllic than she expected, however, and a strange series of events propels her on a quest to uncover her family's French ancestry. Alternating between Ella's story and that of Isabelle Dumoulin 400 years earlier, a common thread emerges that pulls the lives of the two women together in a most mysterious way. Let's hear a sample of this book now, narrated by Laurel Lefcourt.

21:20S4

She was called Isabelle, and when she was a small girl, her hair changed color in the time it takes a bird to call to its mate. That summer, the Duke Dallaglio brought a statue of the virgin and Child and a pot of paint back from Paris for the niche over the church door. A feast was held in the village the day the statue was installed. Isabelle sat at the bottom of a ladder, watching Jeanne Turner paint the niche. A deep blue, the color of the clear evening sky. As he finished, the sun appeared from behind a wall of clouds and lit up the blue so brightly that Isabelle clasped her hands behind her neck and squeezed her elbows against her chest. When its rays reached her, they touched her hair with a halo of copper that remained even when the sun had gone. From that day. She was called La Rose after the Virgin Mary. The nickname lost its affection when Monsieur Marcel arrived in the village a few years later. Hands stained with tannin and words borrowed from Calvin. In his first sermon in Woods, out of sight of the village priest, he told them that the Virgin was barring their way to the truth.

22:31S5

La Rue has been defiled by the statues, the candles, the trinkets. She is contaminated, he proclaimed. She stands between you and God.

22:44S1

So that was The Virgin Blue by Tracy Chevalier. We also have it in Braille, and I think it was a little bit too based on her own family history that she did a bit of research in. The next book is Falling Angels, January 1901, The day after Queen Victoria's Death, two families visit neighbouring graves in a London cemetery. The water houses Revere the late Queen and cling to Victorian traditions. The Colemans look forward to a more modern society. To their mutual distaste. However, the families are inextricably linked when their daughters become friends behind the tombstones and worse, befriend the Grave Diggers Son That's Falling Angels by Tracy Chevalier. It's narrated by Geraldine Brophy and Paul Barrett. Let's have a listen to Geraldine Brophy now.

23:33S6

I don't dare tell anyone or I will be accused of treason. But I was terribly excited to hear the queen is dead. The dullness I have felt since New Year's vanished and I had to work very hard to appear appropriately sober. The turning of the century was merely a change in numbers. But now we shall have a true change in leadership. And I can't help but think Edward is more truly representative of us than his mother. For now, though, nothing has changed. We were expected to troop up to the cemetery and make a show of mourning, even though none of the royal family is buried there. Nor is the Queen to be. Death is there. And that is enough, I suppose. That blasted cemetery. I have never liked it. To be fair, it is not the fault of the place itself, which has a lugubrious charm with its banks of graves stacked on top of one another. Granite headstones, Egyptian obelisks, gothic spires, plinths topped with columns, weeping ladies, angels and of course, urns winding up the hill to the glorious Lebanon cedar at the top. I am even willing to overlook some of the more preposterous monuments ostentatious representations of a family status. But the sentiments that the place encourages in mourners are too overblown for my taste. Moreover, it is the Coleman Cemetery, not my families. I miss the little churchyard in Lincolnshire where Mummy and Daddy are buried and where there is now a stone for Harry, even if his body lies somewhere in southern Africa. The excess of it all, which our own ridiculous earn now contributes to is too much. How utterly out of scale it is to its surroundings. If only Richard had consulted me first, it was unlike him. For all his faults, he is a rational man and must have seen that the urn was too big. I suspect the hand of his mother in the choosing. Her taste has always been formidable.

25:27S1

Falling Angels. And the last book that we have in the collection to mention by Tracy Chevalier is The Lady and the Unicorn, again, based on a very famous work of art, the tapestries. Jean-Louis, a newly wealthy member of the French court, commissions the tapestries to hang in his Chateau Nicola, his chosen designer, meets Leavitt's wife, Genevieve, and his daughter Claude, both of whom take a keen interest in the tapestries. From Paris, Nicola moves to a weavers workshop in Brussels. The creation of the tapestries brings together people who would not otherwise meet their lives, become entangled, and so do their desires as they fall in love. A shunned take revenge, find unrequited love, turn to the church or to pagan ideals. The tapestries become to each an ideal vision of life. Yet all discover that they are unable to make this world their own. So let's hear a sample now of the Lady and the Unicorn, narrated by Cornelius Garrett.

26:27S7

I had proven something with those designs. Leon Levy, you are now treated me with more respect, almost as if we were equals rather than a wealthy merchant tolerating a lowly painter. Though I still painted miniatures, he began to get me commissions from other noble families for tapestries. He shrewdly held on to the paintings I'd made of the six ladies making excuses to Jean Lafitte about returning them, though they were Monseigneur to keep. He showed them to other noblemen who told others. And from the talk came orders for more tapestries. I designed other unicorn tapestries. Sometimes sitting alone in the woods. Sometimes being hunted. Sometimes with a lady. Though I was always careful to make them different from the La Vista ladies. Leon was gleeful. See how excited people are now just with the small designs, he would say. Why do they see the real tapestries hanging in the feasts? Grand Sal. You all have work for the rest of your days.

27:29S1

And that book is also available in Braille. So there we have a few books by Tracy Chevalier. If you'd like to try this very insightful author. And Chevalier is spelled c h e v a l i e. R. That's c h e. V a l. I. E. R and r. Tracy is spelt with a c e y on the end. C e y. That is all we have time for today. I'm Frances Kelland. Thank you for joining us here on here. This if you would like to contact the library for any reason about the books, about joining, about just finding out how you can listen to the books, please give them a call on 1300 654 656. That's 1300 654 656. Or you can email library at Vision Australia. Org. That's library at Vision Australia. Org. I hope you have a lovely week and we'll be back next week with more here this.

Continue listening

On Hear This, latest books in the Vision Australia library. This edition, award-winning Oz fiction.

Australian fiction

Hear This by Vision Australia

4/8/2023

•28 mins

Audio

Books from the Vision Australia library - this episode featuring memoirs and family histories.

Family histories

Hear This by Vision Australia

11/8/2023

•27 mins

Audio

This edition: Michael Parkinson remembered and an assortment of latest books from the Vision Australia library.

Vale Michael Parkinson

Hear This by Vision Australia

18/8/2023

•26 mins

Audio

Hear This reviews latest books from Vision Australia library - this edition starting with two Booker Prize aspirants.

Booker Prize hopefuls

Hear This by Vision Australia

25/8/2023

•27 mins

Audio

Hear This interviews Tracey Chevalier, author of Girl with a Pearl Earring.

Girl with a Pearl Earring

Hear This by Vision Australia

8/9/2023

•28 mins

Audio

Hear This samples a variety of audio books from the Vision Australia library.

Top picks from audio books

Hear This by Vision Australia

15/9/2023

•28 mins

Audio

Events and activities at Vision Australia library - and latest picks from its books.

Community engagement

Hear This by Vision Australia

22/9/2023

•27 mins

Audio

This edition of Hear This from the Vision Australia library opens with a discussion of banned books.

Banned books

Hear This by Vision Australia

6/10/2023

•28 mins

Audio

Hear This features latest books and events at the Vision Australia library.

Latest events and books

Hear This by Vision Australia

13/10/2023

•27 mins

Audio

Latest books from the Vision Australia library - including childhood tales and a John Grisham thriller.

Childhood tales and a Grisham thriller

Hear This by Vision Australia

20/10/2023

•28 mins

Audio

Latest books from the Vision Australia library - including a novel by Australian Sam Drummond.

Oz writer Sam Drummond

Hear This by Vision Australia

3/11/2023

•27 mins

Audio

Books from the Vision Australia library - including a memoir by a friend of Anne Frank.

Anne Frank's friend

Hear This by Vision Australia

10/11/2023

•28 mins

Audio

Book reviews and excerpts from Vision Australia library - including a wartime struggle for survival.

Survival in wartime

Hear This by Vision Australia

24 November 2023

•27 mins

Audio

A special seasonal edition reviews Christmas murder stories available from Vision Australia library.

Yuletide Homicide

Hear This by Vision Australia

8 December 2023

•28 mins

Audio

Veteran talking book reader Tony Porter reviews his many voices.

The many voices of Tony Porter

Hear This by Vision Australia

5 January 2024

•27 mins

Audio

What's new in Vision Australia library of Braille and audio books - including new Australian works.

New Australian books

Hear This by Vision Australia

12 January 2024

•28 mins

Audio

Vision Australia librarian talks of coming events and latest books for people with blindness and low vision.

Coming events and new books

Hear This by Vision Australia

26 January 2024

•28 mins

Audio

Review of books from the Vision Australia library - from a broad international range.

Books from Japan, US, Australia and Sweden

Hear This by Vision Australia

2 February 2024

•27 mins

Audio

New books in the Vision Australia library - from E.L.Doctorow to Alan Bennett.

Reasons Not to Worry, Wild Things... and Alan Bennett

Hear This by Vision Australia

9 February 2024

•28 mins

Audio

Latest events and books from Vision Australia Library, featuring its Community Engagement Co-ordinator.

Vision Library latest with Leeanne

Hear This by Vision Australia

16 February 2024

•28 mins

Audio

Features Jamie Kelly of Vision Australia Library, updating us on its website catalogue. And other new books.

Vision Australia library online, and Jelena Dokic

Hear This by Vision Australia

23 February 2024

•29 mins

Audio

New books in the Vision Australia Library - in this edition, books about paintings.

Books about paintings

Hear This by Vision Australia

1 March 2024

•26 mins

Audio

From the Vision Australia Library, women's memoirs on International Women's Day.

Women's memoirs on IWD

Hear This by Vision Australia

8 March 2024

•28 mins

Audio

Coming events and books at Vision Australia Library for people with blindness or low vision.

Coming events at Vision Library - and a Kerouac classic

Hear This by Vision Australia

15 March 2024

•29 mins

Audio

Latest books from Vision Australia Library - this week, some top Oz and worldwide novels.

Top Oz and world novels

Hear This by Vision Australia

29 March 2024

Audio

Coming events at Vision Australia Library in connection with the Melbourne Writers' Festival.

Melbourne Writers' Festival

Hear This by Vision Australia

5 April 2024

•28 mins

Audio

Coming events and new books at the Vision Australia Library for blind and low vision people.

Event update and more new books

Hear This by Vision Australia

12 April 2024

•29 mins

Audio

How printed works are brought to life as audio books in the Vision Australia Library.

Audio book narrators

Hear This by Vision Australia

19 April 2024

•28 mins

Audio

ANZAC Day edition of this series from the Vision Australia library for people with blindness or low vision.

ANZAC sniper

Hear This by Vision Australia

26 April 2024

•28 mins

Audio

From the Vision Australia library: a South African childhood, AI issues and an American First Lady.

Apartheid, AI and Michelle Obama

Hear This by Vision Australia

3 May 2024

•27 mins

Audio

Forthcoming Vision Library events including those connected with the Melbourne Writers' Festival.

Melbourne Writers' Festival and Vision Library events

Hear This by Vision Australia

10 May 2024

•28 mins

Audio

Murder mystery novels available from the Vision Australia library are reviewed and sampled.

Murder mysteries

Hear This by Vision Australia

24 May 2024

•27 mins

Audio

Celebrating National Reconciliation Week with books from Vision Australia Library... plus some user favourites.

Reconciliation Week and Reader Recommends

Hear This by Vision Australia

31 May 2024

•27 mins

Audio

Reader Recommends and crime fiction from the Vision Australia library for blind and low vision people.

This Other Eden... and some other readin'!

Hear This by Vision Australia

7 June 2024

•29 mins

Audio

Vision Library's coming community events and latest books for people with blindness or low vision.

Coming events and latest books

Hear This by Vision Australia

14 June 2024

•29 mins

Audio

Books in Vision Australia library for people with impaired vision - this time on the theme of Darkness.

Darkness

Hear This by Vision Australia

21 June 2024

•29 mins

Audio

New books in Vision Library including the Wikileaks founder's autobiography.

Julian Assange - by the man himself

Hear This by Vision Australia

28 June 2024

•29 mins

Audio

Community events soon to happen at Vision Australia Library for people with blindness and low vision.

Coming events at Vision Australia Library

Hear This by Vision Australia

5 July 2024

•28 mins

Audio

Two well-known authors open the latest look at new publications in the Vision Australia Library.

Hilary Mantel, Bret Easton Ellis and more

Hear This by Vision Australia

19 July 2024

•27 mins

Audio

Vision Library series, this episode features new Australian crime novels written by women.

Australian sisters in crime

Hear This by Vision Australia

26 July 2024

•28 mins

Audio

Latest publications in the Vision Library, starting with a biography of John Farnham.

He's the Voice

Hear This by Vision Australia

2 August 2024

•27 mins

Audio

Latest reviews and readings from publications in the Vision Library for people with print disabilities.

Race, history and Black Ducks

Hear This by Vision Australia

9 August

•28 mins

Audio

Books from Vision Library reviewed include a Julie Andrews memoir, Guardian newspaper picks and more.

Julie remembers and The Guardian recommends

Hear This by Vision Australia

30 August 2024

•27 mins

Audio

An Australian author discusses her works, plus reviews of other books in the Vision Library.

Jane Rawson - author

Hear This by Vision Australia

6 September 2024

•28 mins

Audio

Update on forthcoming events and available publications at the Vision Australia Library.

What's On at Vision Australia Library

Hear This by Vision Australia

13 September 2024

•27 mins

Audio

Accessible Vision Library books reviewed, including murder mysteries and award nominees.

Mysteries and prize contenders

Hear This by Vision Australia

20 September

•27 mins

Audio

Reviews and events at Vision Australia Library to mark World Sight Day, October 10.

World Sight Day and Barbra Streisand

Hear This by Vision Australia

4 October 2024

•28 mins

Audio

What's on in the Vision Library, and the works of Ira Levin and Han Kang.

Library events, Ira Levin and Han Kang

Hear This by Vision Australia

11 October 2024

•28 mins

Audio

Vision Library publications reviewed - opening with some tributes to writers passed.

Tributes, and more

Hear This by Vision Australia

18 October 2024

•28 mins

Audio

Reviews and readings from Australian, British and US books in the Vision Australia Library.

Tomorrow, Questions, Mistresses and Murder

Hear This by Vision Australia

25 October 2024

•28 mins

Audio

Reviews and readings from books available in the Vision Australia Library.

From Australian thrillers to the US and South Africa

Hear This by Vision Australia

1 November 2024

•28 mins

Audio

A wide range of books in the Vision Australia Library are reviewed and sampled.

Leonard Cohen, ghosts and Broken Hill

Hear This by Vision Australia

8 November 2024

•28 mins

Audio

Events and publications at Vision Australia Library for people with blindness or low vision.

Vision Library: what's in and what's on

Hear This by Vision Australia

15 November 2024

•28 mins

Audio

Interview with an award-winning author about her life and work... plus more publications in the Vision Australia Library.

Jacqueline Bublitz

Hear This by Vision Australia

22 November 2024

•28 mins

Audio

Vision Australia Library for people with vision impairment updates its coming events and latest publications.

Coming soon to the Vision Library

Hear This by Vision Australia

13 December 2024

•28 mins

Audio

Christmas-themed books in the Vision Australia Library for people with vision impairment.

Christmas offerings

Hear This by Vision Australia

20 December 2024

•28 mins

Audio

New books for 2025, fiction and non-fiction - vale Leunig!

Fiction and non-fiction for the New Year

Hear This by Vision Australia

3 January 2025

•27 mins

Audio

Reviews of varied books from the Vision Library - some centring on radio stations or radio plays.

Radio drama

Hear This by Vision Australia

10 January 2025

•29 mins

Audio

What's On at Vision Australia Library - and latest publications accessible to people with blindness and low vision.

Coming events in 2025 - and latest publications

Hear This by Vision Australia

24 January 2025

•28 mins

Audio

Writings on Marianne Faithfull and award-contending works in the Vision Australia Library are reviewed.

Vale Marianne... and award-nominated books

Hear This by Vision Australia

31 January 2025

•28 mins

Audio

Special guest highlights interesting events in libraries around the country... and some new books.

What's new in libraries around Australia

Hear This by Vision Australia

7 February 2025

•27 mins

Audio

Accessible publications chosen for February 14: Library Lovers' Day, Valentines Day and World Radio Day.

Library Lovers' Day

Hear This by Vision Australia

14 February 2025

•29 mins

Audio

An update on Vision Australia Library's coming events and latest blind-accessible books.

Coming events and new books

Hear This by Vision Australia

25 February 2025

•29 mins

Audio

Reviews of accessible books including a John Steinbeck classic, and news of a forthcoming writers' festival.

Brimbank and Steinbeck

Hear This by Vision Australia

28 February 2025

•29 mins

Audio

Coming courses and other events at Vision Australia Library - and latest accessible books.

Courses, events and latest publications

Hear This by Vision Australia

14 March 2025

•28 mins

Audio

Special with interviews and readings at a writers' festival and writing competition in Melbourne.

Brimbank Writers' and Readers' Festival and Micro-fiction Competition

Hear This by Vision Australia

21 March 2025

•30 mins

Audio

An interview with an Australian woman writer and reviewer, about her favourite female authors.

Women authors with Stella Glorie

Hear This by Vision Australia

28 March 2025

•29 mins

Audio

Reviews and excerpts from accessible works in the Vision Australia Library, starting with a new Australian novel.

Reader recommends a Deal

Hear This by Vision Australia

4 April 2025

•27 mins

Audio

Vision Australia Library brings news of accessible events at the forthcoming Melbourne Writers' Festival.

Melbourne Writers' Festival 2025

Hear This by

11 April 2025

Audio

Vision Australia Library pays tribute to the late Australian author of the Miss Fisher mysteries and more.

Vale Kerry Greenwood

Hear This by Vision Australia

18 April 2025

•28 mins

Audio

ANZAC Day special featuring reviews and short readings from books about the First World War.

Reading about World War 1

Hear This by Vision Australia

25 April 2025

•28 mins

Audio

Reviews and readings of user favourites in Vision Library - including an Antarctic adventure.

Reader recommended

Hear This by Vision Australia

2 May 2025

•28 mins

Audio

What's accessible in the Vision Australia Library - including new books by Kate Grenville and Eric Idle.

Always look on the bright side of... time and place

Hear This by Vision Australia

9 May 2025

•29 mins

Audio

First part of an interview with an Australian author, military historian and war veteran.

Barry Heard's true tales of war (part 1)

Hear This by Vision Australia

16 May 2025

•28 mins

Audio